The Feral Gardener by Alyssa Thorne

LIT ANGELS #25: MOTHER. EARTH.

Table of Contents:

Robbins Place by Kate Marra

Starlight, Starbright by Narasu Rebbapragada

Mother of The Forest by Ophelia Guerdad

Bad Mom by RoseAnn Fino

Twenty-One Years by Robin Carr

Galaxies by Stephanie Callas

At The Doorway of Dreaming by Alyssa Thorne

Edited by Francesca Lia Block

Copyedited by Kerby Caudill

Art by Alyssa Thorne

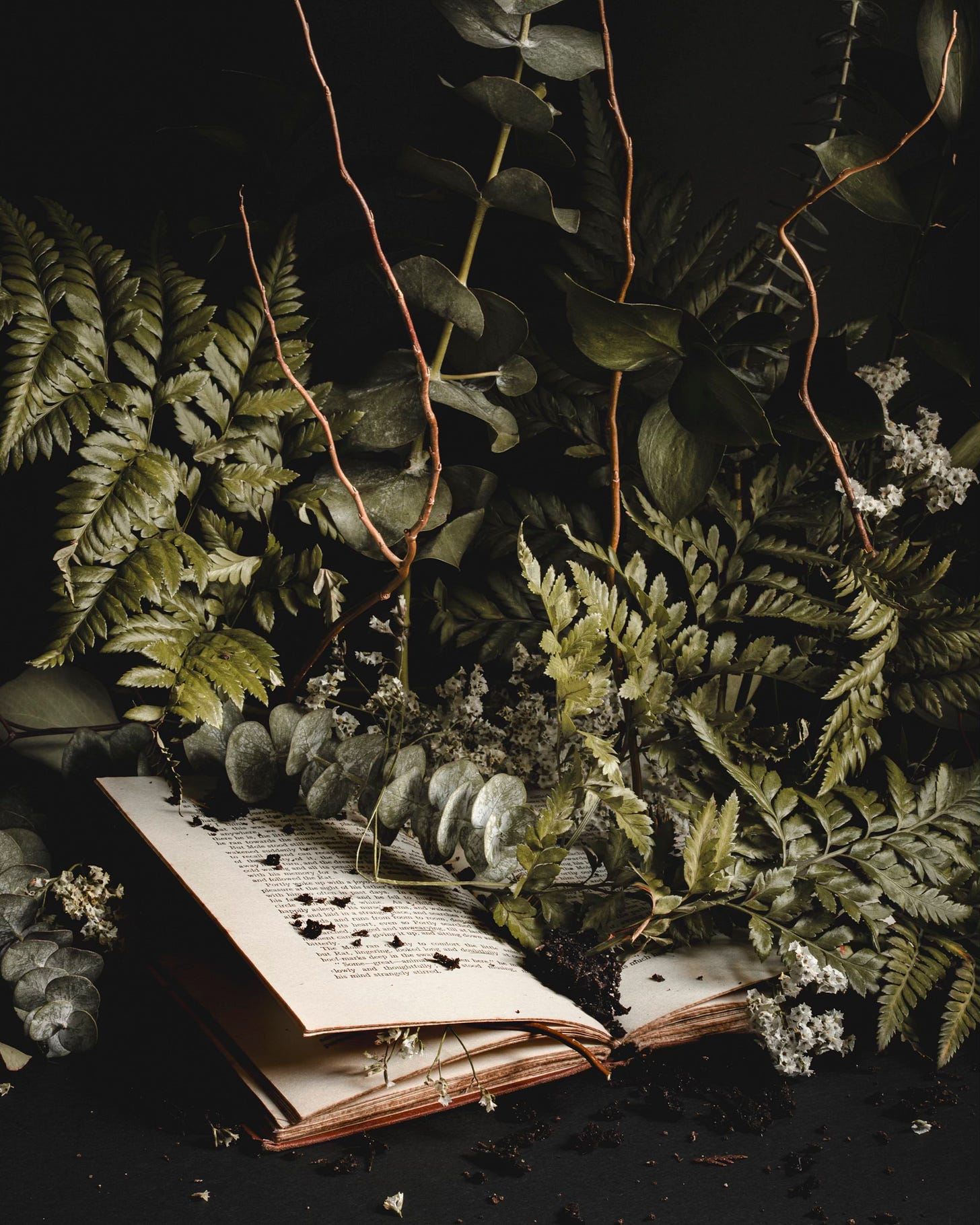

Hinterland Overgrowth by Alyssa Thorne

Robbin’s Place

by Kate Marra

Driving with a newborn through hundreds of miles of boreal forest wasn’t as straightforward as Cherie thought it would be, but it wasn’t entirely difficult either. There had been a room of maybe donated things at the hospital and Cherie took a car seat and a yellow blanket with blue, thickly stitched edges and Delphi mostly slept there in the back seat, facing the past that Cherie mumbled about to her; while she drove she mumbled about that asshole, all those fish, reeking of fish, the dark sky, that religious woman Ashley and the bright constant, cruel day.

Delphi listened and she sometimes opened her black eyes in secret since she was in fact looking backwards, where Cherie couldn’t see her. Delphi saw the weak almost daylight through the thin waffles in the yellow blanket that had fallen over her eyes and she heard words, muffled and fast and sweet, perfect words! And she thought, this is it! Because she was awake and in life and a smell sour and wild blew through the cracked window and she put her tiny hand against the window, to be and run and smell like that wild thing out in the yellow world as Cherie said, “Excelsior! What the fuck is that?”

Because a few nights before she had Delphi, Cherie had gone down to Mecca, the bar, and Delphi’s dad was there. A lot of people were there, but Delphi’s dad was there and so was a woman, a teenager. She had looked right at Cherie face, trusting, smile crooked and young. Cherie had said to Delphi’s dad, “This better be your fucking daughter.” Delphi’s dad said it was Janet. Janet said hi. Cherie had on Kirkland brand “Uggs," a khaki jacket with grey fake fur around the hood, nine months of Delphi.

Janet had a black T-shirt on that said The Hills have Eyes. She had black nails, a round plump mouth and Kirkland brand “Uggs," sagging and salt stained at the sole. She turned around and leaned over the bar and she had on a red thong that tied into bows on the sides and the tattoo on her lower back said Excelsior!

“Excelsior!” Cherie said with the appropriate inflection like, a wizard conjuring a spell, and Cherie had seen Delphi’s dad’s eyes as they read over the tattoo, not for the first time. Cherie had seen Janet order a drink, chew on an ice cube, tuck smooth, black hair behind a little shell ear. Cherie had left, she had shuffled through the navy night. Everyone knew it was warmer when there were no stars. She said to Delphi, “Excelsior, some kind of sword bullshit, some kind of bullshit fit for the king of nothing.”

Cherie was getting jumpy. She had been so good, so good for nine months. Well, she had been watched, tested and not trusted. She was a trustworthy person. “To think,” she said to Delphi, “that I thought that people who chose to suffer in this horrible fucking tundra were closer to God, that it made you think, being cold and dark all the time. It just gives you a Jesus complex, it just makes you …” and she looked at Delphi. “Well, I won’t say it.”

Delphi didn’t hear her mother. Delphi’s eyes were closed, she was asleep, that moment; the one with the yellow evening light of the day, with the cold smooth touch of the window, with the wild so close, just behind the glass reaching out to her. She never remembered that moment again.

Cherie thought that Excelsior was a sword.

It was not.

As they drove, the trees thickened, and the ice weakened. Paws and antlers shrank. Cherie and Delphi stopped and drove on. Darker night into lighter, still dark day.

Cherie saw a sign for E.T. Lake. Phone home, she said, on repeat, every three or five minutes for two hours. Around mid-day she heard Delphi squeak and Cherie also saw what looked like a little slow and flapping snowball in the middle of the road. Cherie wasn’t a nature freak, that was more Sydney’s thing, she thought. But she was a mother now, and in front of her stopped car was a baby something. It was an eaglet. Bald eagles lined the highway for miles. Too many to count, but some people tried. Some kept a running count because they had nothing better to do, thought Cherie. “Phone home,” she said, to the eaglet, while she leaned out of the driver’s side, door half open. The bird just kind of looked up at her, with what Cherie thought was extreme attitude. Whatever, she thought but she thought it looked like Delphi, actually, black, little beads for eyes and tufts of hair going this and that way. “Okay,” she said and, leaving the car door open and the car stopped in the middle of the road she walked out, took off her purple hoodie and wrapped it around the bird. She put the bird where the feet go, at the bottom of the front seat, and she pulled over at the next rest stop. It was called Angry Moose or Hungry Bear, or Lost Eaglet, or some generic bullshit. Cherie grabbed the eaglet, and left Delphi because God would look after her. But Cherie still kept an eye on the car as she walked up to some men at the front of the rest stop.

“Hi,” Cherie said. There were three men, they looked the same except one was old, one was young, and one was neither. “Do you know, is there a veterinarian?”

“Here,” said the old one.

“Well, obviously not here,” Cherie said. “But, around.”

“No,” said the old one.

“If you need tranq,” said the young one, “you can just ask.” Cherie considered this. She looked at the young man who was so familiar to her; he looked like they all did. Hard, skinny neck. Dirty face, red eyes.

“You look well and run ragged,” said the old one.

“You look like shit,” Cherie said. All three men laughed. “I need a veterinarian.” she opened the hoodie to show the men the bird. “Or someone, I don’t know.”

Delphi opened her eyes in the car, opened them to silence.

“Oh,” the middle-aged guy said. He looked at Cherie and it was a kinder look, human to human. not transactional. “Robbins can help you out with that.”

“Robbins, thanks,” Cherie said. “Very relieved this is cleared up then.”

“He has a wildlife rehab place, that way, I don’t know, fifteen or so kilometers.” He studied Cherie. “You’re not AAFC are you?”

“What the fuck,” Cherie said.

“They’re trying to shut him down,” said the middle-aged man. “Send vets out there every other week, but those animals, they’re well and fed and everything, they’ll get him soon enough.”

“I’m anti-government,” Cherie said.

“You’re something,” the old man said. “You need a shower.”

“He’s got a wolf out there, not a mix. A black wolf,” said the young one. “He don’t use shock collars or anything like that.” The eaglet had started to move; it was wiggling in the hoodie. “Imagine if you could use those on your kids,” the young one said and laughed.

Cherie didn’t smile, she looked back at her car, but the window reflected the gray sky, the wet pavement. Delphi wouldn’t go anywhere.

“We had worse as kids,” said the old one.

“Okay,” Cherie said. “That way,” she pointed down the road, left.

“One way in and one way out,” said the middle aged one. “Just, I don’t know, tell him Rick sent you. Do you have a gun?”

“No,” Cherie said.

“He does,” said Rick. “You’re not RCMP?”

“If I was, I’d have a gun,” said Cherie.

“And some weight on you,” the old one said.

“You like big girls?” asked Cherie.

“You bet,” said the old one.

“You like skinny guys?” the young one asked.

“Rich ones,” said Cherie as she walked away.

“I wish I could use those shock collars on my kids,” the young one said but Cherie didn’t hear him. The men’s voices and some pine needles were picked up by the wet green wind.

Robbin’s wildlife place had a sign in front, with moose antlers, some skulls. It was hand painted; it said WILDLIFE REHAB. It said KEEP OUT. It said, AAFC, FUCK OFF, it said WOLVERINE SKULL, with an arrow pointing to a skull. The fence was a brown metal cattle fence, the plants overtaking it were maidenhair, fuzzy as the eaglet’s and Delphi’s head, salal shiny green and smooth. Cherie held Delphi in one arm. She had the eaglet in an empty backpack which she held by the top handle, let it hang. She shrugged and unhooked the chain that kept the gate shut, listened to the clang roll through the dark, wet forest. Everyone knew: these nights were warmer without stars and the clouds kept the noise in, held it there.

She didn’t think twice that her daughter could be eaten by Robbin’s wolf; actually, the thought didn’t cross her mind at all. She did wonder why she was going through this trouble for the little eaglet. She thought, it must be her motherly instinct kicking in. No other explanation; she never was even that close to the dog.

“Stop,” said a man holding a live stoat, and an automatic weapon.